Cast Into the Abyss.. Untold stories of civilians swallowed by secret detention centres in Sinai

Executive Summary

“Now that terrorism’s over in North Sinai, it’s my basic right to know where my son is-whether he’s alive or dead. I don’t mind sending telegrams to any government office in Egypt, or a complaint to the UN, or anything-even if they arrest me. What, are they going to stop me from looking for my own son too?”

The father of one of the forcibly disappeared

“There are nine core international human rights treaties, and Egypt is a party to eight of them. The only treaty Egypt has not joined is the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. The crime of enforced disappearance carries extremely negative connotations and implications. However, this could be addressed, and such accusations could be removed from our record.”

Ambassador Moushira Khattab, former president of the National Council for Human Rights in Egypt

In November of 2024, the Sub-Committee on Accreditation (SCA), affiliated with the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI), responsible for assessing institutions’ compliance with the Paris Principles, adopted its recommendations to downgrade the National Council for Human Rights in Egypt to B status, expressing serious concerns about the Council’s lack of independence, effectiveness, and transparency, as well as its failure to address issues such as enforced disappearances and arbitrary arrests.

Over the past decade, the Egyptian state has pursued a systematic policy of oppressive security measures in the Sinai Peninsula, most notably through sweeping campaigns of arbitrary arrests that have targeted thousands of men, women, and children. Many of those detained were subjected to brutal torture during varying periods of enforced disappearance. Some eventually resurfaced in prisons or returned to their families, others were extrajudicially killed, while many remain unaccounted for, with their families still unaware whether they are alive or dead. All of this formed part of the security approach adopted by the authorities and the military in their confrontation with armed Islamist groups since 2013.

This report documents 82 ongoing cases of enforced disappearance, representing a portion of the 863 cases of individuals whose fate remains unknown to this day, as recorded by the organisation in its various reports over the years. This figure does not constitute a comprehensive tally of all those forcibly disappeared in Sinai, but rather reflects the cases that the organisation has been able to verify and document.

Meanwhile, a representative sample of activists and tribal figures in Sinai estimate that the number of forcibly disappeared persons ranges between 3,000 and 3,500, based on a methodology that involved engaging the local community in assessing the scale of the phenomenon for the purposes of this report. Additionally, one of the interviews conducted by the organisation with the father of a forcibly disappeared person revealed that the serial number assigned to his son’s details by an initiative affiliated with the Al-Waseem Charitable Association (A civil society organisation linked to businessman Ibrahim Al-Argani, known for his close ties to the military and intelligence agencies) was 2,870.

These policies did not emerge overnight; rather, they are rooted in a long history of repressive security practices against the local population, which became clearly visible after the Taba and Ras Shaitan bombings on 7 October 2004. The attacks killed 34 people and injured over 100 others, including tourists and local residents. In response, the Egyptian authorities launched wide-scale arrest campaigns across North Sinai. On 25 October 2004, the Ministry of Interior announced that it had identified nine suspects: five were already in custody, two had reportedly been killed during the attack, and the remaining two were still at large.

Despite the limited number of individuals officially accused of carrying out the attacks, Egyptian authorities arrested over 2,400 local residents at the time. Human rights reports by Egyptian and international organisations stated that these arrests were arbitrary and abusive, violating the law, as they were not limited to suspects but extended to their relatives, including women and children, in what resembled collective punishment. Hundreds of detainees were subjected to enforced disappearance in unofficial or undisclosed detention sites for prolonged periods without judicial supervision or any means of contacting the outside world. This stark disparity between the actual number of accused and the scale of mass arrests reflects a longstanding security approach based on broad suspicion and collective punishment, which led to grave human rights violations.

A 2005 report issued by Human Rights Watch on the mass arrests and torture following the 2004 Taba bombings presented credible evidence that detainees were subjected to systematic torture, particularly at State Security Investigation facilities. The report documented the use of severe methods such as electric shocks, severe beatings, and suspension by the limbs. It stated that Torture was systematic in State Security facilities during interrogations, with consistent reports of the use of electric shocks, beatings, and suspension. The report also noted that these grave violations were committed with impunity, as no investigations were opened against the security officials involved, and no one was held accountable. Meanwhile, Egyptian human rights organisations reported that security forces arrested around 3,000 individuals, including several hundred who were detained solely to pressure wanted relatives into surrendering themselves.

These facts reflect that since 2004, and possibly even earlier, the Egyptian state has regarded the Sinai Peninsula as a perpetual security risk, thereby legitimising repressive security policies that expanded after 2013. Although the context and the groups involved in the violence differed between the two periods, the state relied in both instances on the same security approach—based on exceptional laws and systematic violations of rights. What was initially implemented as exceptional measures following the 2004 Taba bombings transformed, since 2013, into an institutionalised system of repression, wherein practices such as enforced disappearance and extrajudicial killings became systematic, amid a complete absence of accountability and the continual expansion of the security agencies’ authority.

What is striking in the comparison between the two periods is that the level of violence and the nature of the violations remained fundamentally unchanged; however, they became more widespread and sustained after 2013. This was accompanied by the weakening of the role of the civilian judiciary and the increasing involvement of military courts in trying civilians, thereby providing a legal cover for these violations. This comparison reflects a progression from a temporary state of repression following a security attack to an entrenched authoritarian model characterised by the excessive use of force and systematic enforced disappearance, all occurring amid a lack of transparency, oversight, and accountability. This situation places the Egyptian state under serious legal and ethical obligations towards the victims.

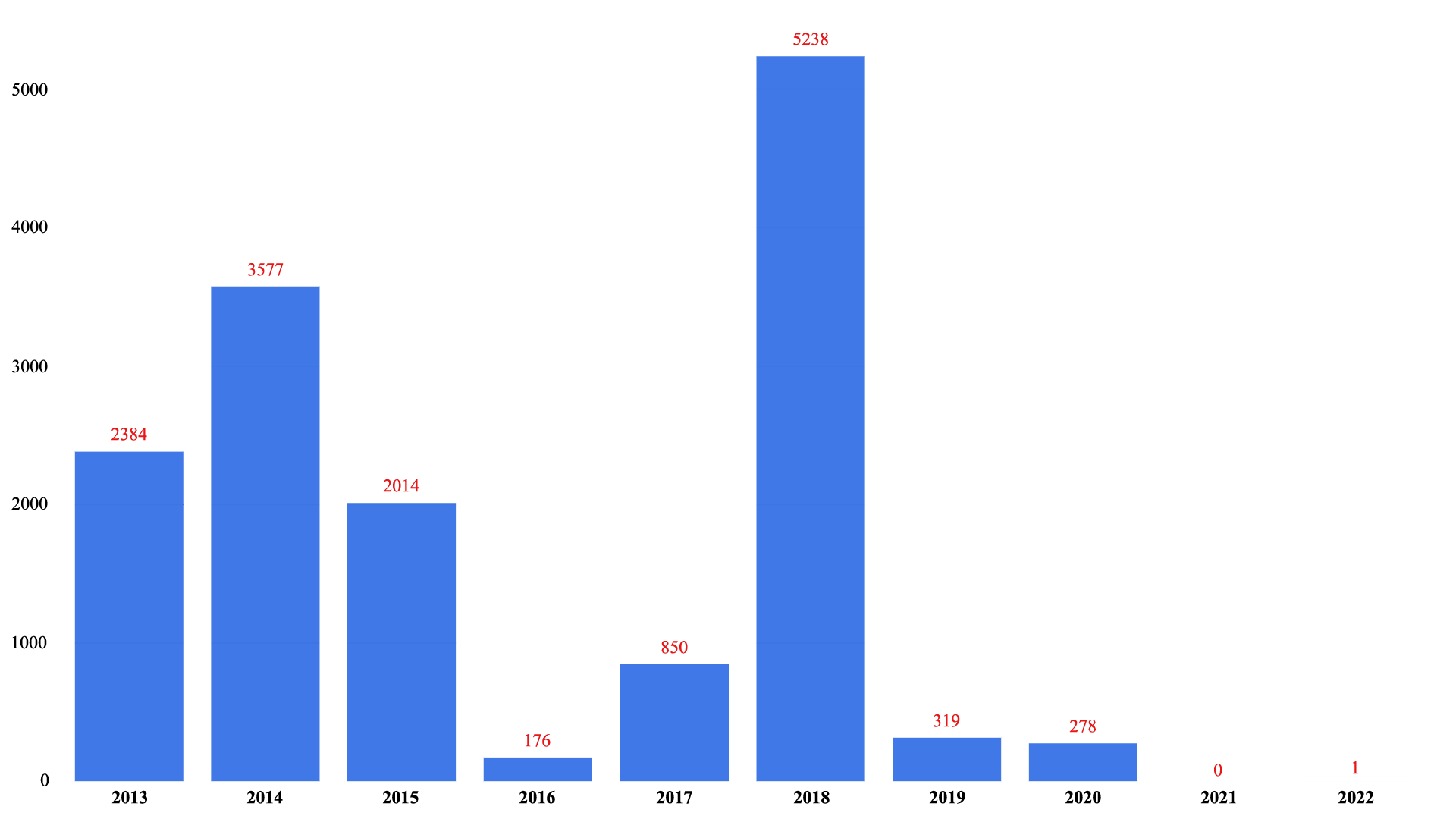

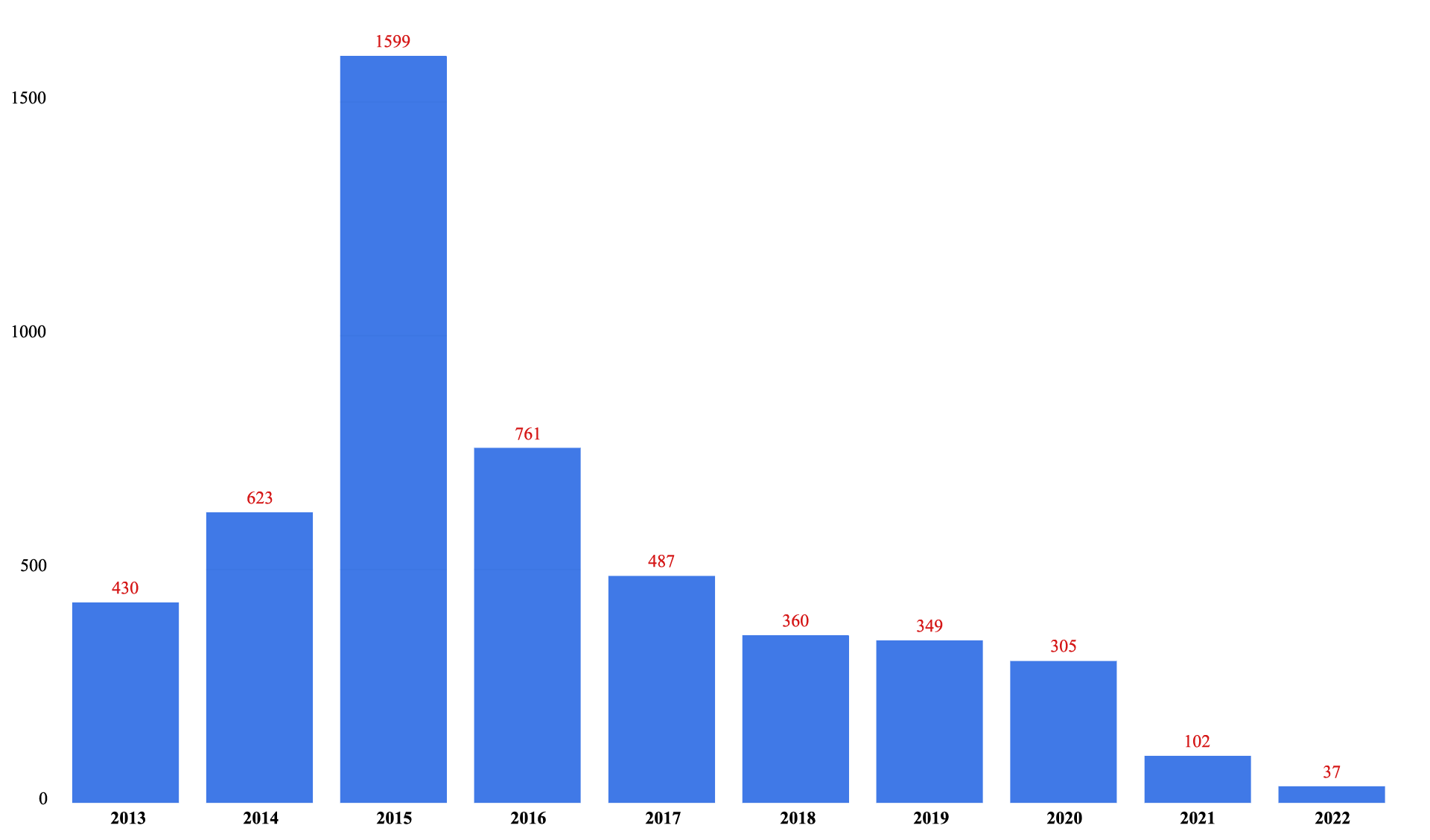

As part of this report, the foundation’s researchers created a database based on a review and analysis of official data issued by the spokesperson of the Egyptian Armed Forces during the period of military operations spanning from 2013 to 2022. These data revealed that the Armed Forces announced the killing of 5,053 individuals described as “terrorist elements,” and the arrest of 14,837 others suspected of belonging to armed groups. These official figures starkly contradict estimates of the number of militants affiliated with extremist groups in Sinai, which ranged, according to the West Point Counterterrorism Center (CTC), between 1,000 and 1,500 members as of mid-2018, while the RAND Corporation estimated them at merely “several hundred.” This discrepancy raises fundamental questions about the fate of thousands of detainees whose place of detention or ultimate fate remains unknown to this day.

It is worth noting that these figures do not include data issued by the Egyptian Ministry of Interior, which in turn accounts for a significant portion of arrests and extrajudicial killings. For example, on 15 March 2018, the Interior Ministry’s spokesperson announced that, during the period from February 9 to March 15, 2018 (only 35 days), police forces had “screened 52,164 individuals, who were apprehended based on suspicion and released those whose position was deemed sound,” without specifying the number of those actually released. This clearly indicates the expansion of detention campaigns based on suspicion, without providing clarity on how many individuals were in fact released. This clearly points to the arbitrary and widespread nature of suspicion-based arrests, and reinforces concerns about the fate of an unknown number of individuals in the absence of transparency and accountability.

A column chart illustrating the number of detainees reported by the military spokesperson between 2013 and 2022.

A column chart illustrating the number of fatalities reported by the military spokesperson during the same period.

To read the full report, please download or view the attached file.